Ainsworth, Maryan W. 'Religious Painting from about 1420 to 1500: In the Eye of the Beholder.' In From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Edited by Maryan W. Ainsworth and Keith Christiansen. Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1998: 79, 81-82, fig. Professor Ron Oliver, Edith Cowan University, AJET Editor 1997-2001. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder Roger Atkinson To begin with, there is a logical.

In the Eye of theBeholder- ロン・オリヴァー (Ron Oliver) はロンドン生まれ、イギリスの写真家。 18歳で高校卒業とともに写真家としてのキャリアを積む。児童ポートレートをもっとも得意とする。代表作に『In The Eye of a Child.』(1995年)など。.

- Eye of the Beholder (1999) SoundTracks on IMDb: Memorable quotes and exchanges from movies, TV series and more.

- Eye of the Beholder Download Eye of the Beholder I,II,III - The Forgotten Realms Archive - Collection One @ GOG.com (buy):: Eye of the Beholder is a dungeon crawler RPG with a first-person perspective based on the 2nd Edition AD&D rules. Your starting party consists of four characters and up to two NPCs can join later.

Eye Of The Beholder Maps

John Tozer

The uproar and hyperbole that accompaniedthe pre-release of Adrian Lyne's recent filmic adaptation of Lolita came,in the light of recent similar media-propelled moral panics, as no realsurprise. Determined to maintain its tradition of sanctimonious over-reaction,last April the Daily Mail ran the front page headline 'Lolita actor sparkschild sex storm', with 'Jeremy Irons in child abuse storm' writ large acrosspage seven inside.1 Theintended ambiguity of both headlines is representative of the chronicallyconfused and often hypocritical attitudes of commentators on both publicand private depictions of children. In the light of this the followingis intended not only as a brief study of Lolita, both Nabokov's and AdrianLyne's, but as an attempt to sort through and make sense of some of thetangled threads of fact, fiction and biased opinion that gather aroundmany representations of children today.2

Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita concernsthe unusual relationship between thirty-something Humbert Humbert and twelveyear old Dolores Haze. Driven by memories of a passionate but unconsummatedadolescent relationship with a girl named Annabel, Humbert pursues theghost of his first love until twenty five years later he finds Lolita,who to Humbert's inflamed senses is the embodiment of the 'certain initialgirl-child' with whom he was smitten as a boy. His infatuation graduallyturns to obsession, but at the age of fourteen Lolita deserts him for apathological deviant and pornographer named Quilty, who in due course shealso leaves. The two are briefly re-united after three years when Humbertfinds Lolita married, heavily pregnant and adamantly un-interested in himand his protestations of love. Humbert tracks down and kills Quilty thendies of heart failure in prison, and Lolita, having produced a still-borndaughter, dies in childbirth.

Though it is the sexual relationshipbetween Humbert and Lolita that seems to receive the most attention acrossthe media spectrum, Nabokov's novel is not primarily concerned with thenotion of old men and little girls, though many would like to think itis, as simplistic interpretations are often easier to digest than thosethat are more complex. Instead there is within the book an implicit subtextthat can only be grasped from an engagement with the novel in its entirety.Ultimately the underlying theme of Lolita is not that of the relationship,sexual or otherwise, between a grown man and a child, but is concernedwith that of the reader and the level of his or her sympathy with whatoccurs between the book's two main protagonists. Lolita is about how toswathe a story of child abuse in dazzling and brilliant packaging to makeit acceptable, even agreeable. It is about the often difficult balancebetween art and morality; a challenge to the reader to form an allegiancewith a problematic point of view and to adopt a moral position based noton whether child abuse is acceptable, (for we all know that it can neverbe so), but upon whether art is a sufficient excuse for writing a storyabout a man who is imprisoned ultimately for murder and not for his immoralactivities with a young girl. We as readers must weigh the pleasure weget from Lolita, and our belief that it is a 'great novel', against theknowledge that, despite the 'fancy prose style', it tells the story ofa grown man's physical and emotional obsession with a child.

Where Adrian Lyne's Lolita failsis, despite what the press have had to say, in his use of a young actresswho does not appear taboo enough to duplicate the dynamic of the book:because Dominique Swain, fifteen when making the film, appears not as apubescent girl but as an averagely sexy teenager Nabokov's point is lost.In some respects Lyne's Lolita is successful in its evocation of the tragedyof a relationship that is doomed from the start, and one leaves the filmalmost wishing that the two could live happily ever after, but this effectivelydestabilises the fragile balance achieved in the book between the sympathyelicited by the tragic figure of Humbert and the moral unease of the readerat the notion of an adult male physically possessing a twelve year oldgirl.

In effectively censoring Lolitain this way Lyne has in fact been unfaithful to the novel, and has reliedheavily on the notorious character of the book, and the predictable wrinklingof the public's nose at any whiff of problematic sexual scandal, in orderto inject the troublesome element of sensationalism that the film lacks.One should not be surprised, though, at Lyne's reluctance to use a childin his film, as he as well as anyone else must be aware just how difficultit would be for an audience to witness some of the scenes in Lolita playedby an authentically young actress.

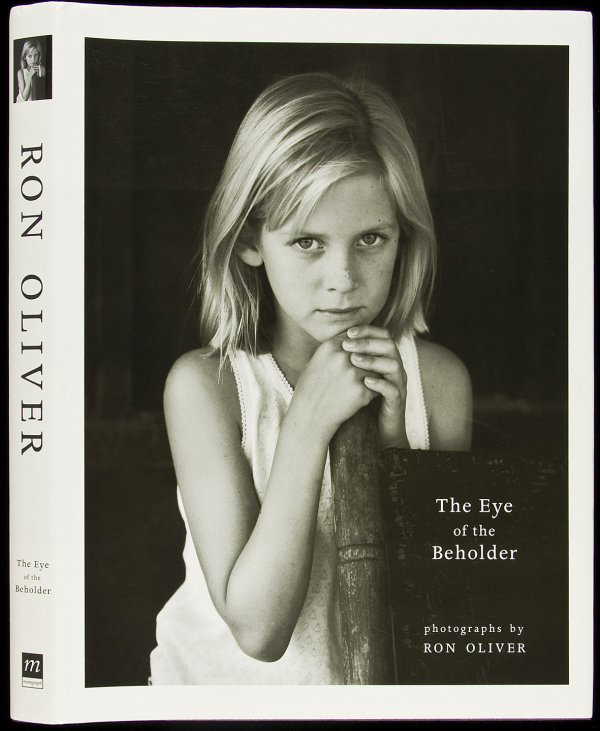

Depictions of the body, and particularlythe bodies of children, present a dilemma for both artists and commentators,and often photographers who work with children, like Jock Sturges, SallyMann, Graham Ovenden or Ron Oliver, are discussed almost entirely in termsof the works' uncertain legal status and the fact that the images may beopen to classification by some as pornographic, not due to their intrinsicvisual content, but to a woefully, (and perhaps inevitably), inadequateset of categorical laws that may vary from country to country or from stateto state.

However, what defines the statusof images, or what enables them to produce meanings, is not necessarilytheir formal denotative qualities, but the connotative meanings and messagesthat are constructed by the nature of the field through which they arerealised or consumed. An image such as Robert Mapplethorpe's Rosie maynot be dissimilar to images that may be found within a small number ofthe Internet's pornographic newsgroups but is not in itself pornographic.Rosie the image was described by moralists in 1996, shortly before it waswithdrawn on the advice of the police from the Hayward Gallery's RobertMapplethorpe retrospective, 3not only as 'child pornography' but as 'utterly horrific'. This howeverdoes a disservice not only to Rosie the child, in describing her imagein this way, but to Mapplethorpe the photographer, as although he wouldhave been aware that the image was certainly striking, not least in theintensity of the child's gaze, Rosie is, in the context of the rest ofhis oeuvre, a moderate and compassionate depiction of humanity.

What seemed to be overlooked orignored by the majority of commentators at the time was that in order foran image such as Rosie, (or the family photographs of the newscaster JuliaSommerville's seven year old child at bath time, held by a member of Bootsprocessing staff to be obscene), to be seen as pornographic the viewermust project a pornographic sensibility onto it. So despite the fact thatRosie clearly has her childish genitals on view, they can only be seenas pornographic, (and by extension erotic), by an individual who has apredisposition to seeing them in that way, whether they be paedophilesor moral crusaders. To anyone of a rational sensibility Rosie is just astriking photograph of a little girl who happens not to be wearing anyknickers.

Censoring images of children likethis is, for a number of reasons, likely to do more damage in the longrun than good. Firstly, in condemning all images of naked or semi-nakedchildren to the status of child pornography one is not preserving the innocenceof childhood but removing it, and casting all children in the role of potentialtempters and temptresses; destined forever to be seen within the public'simagination not as young people on the path to maturity but as individualsforced to belong to the world of grown-up fantasies and neuroses beforetheir time. Even a recent television advertisement for the Yellow Pagesshowed two new-born babies with their infant genitalia judiciously castin digital shadows in order that they should not offend.

There is a danger, with the increasingattempts of some pressure groups to promote the belief that any depictionof youthful nudity is inherently unhealthy or bad, that one may no longerbe able to see a naked child for what he or she is but instead become accustomedto seeing a body sexualised in adult terms; consequently, the childishbody, both clothed and unclothed, is in danger of being fetishised andturned into a routine container of adult sexual values. In addition toand as an effect of this, in their desire to depict children as existingin some pre-Fall Edenic state the activities of some child care groupsare, by insisting that they are non-sexual beings, actively denying childrenthe right to their own, non-adult, sexuality; to the sexuality that ispart and parcel of being human at any age.

Social constructions of pubertyand adolescence will inevitably dictate the extent of the problems thatare perceived to exist within the welfare and protection of children. Whensomething arrives to disrupt the 'normal', 'healthy', received social stereotypesof how children should fit into the spaces set aside for them by society,as with the work of Jock Sturges, Ron Oliver or Sally Mann,4it has tended to come under fierce attack from individuals or organisationswho perceive it as a threat; not just to children but to the social orderitself. But, as the welfare of children is, rightly, high on our moralagenda, it should not be surprising that there should be those who areprepared to question the role that children have within the culture, sexualor otherwise, of our society. Those who maintain that children have norole within sexual narratives are, I would suggest, not helping to solvethe problem but in fact adding to it. In seeking to censor debate aroundaspects of the lives of children our attitudes and understandings of 'sensitive'subjects will remain stifled, and discourses that may prove to be of valuewill, because many find them unpalatable, remain unarticulated.

The objects and methods of censorshipare dictated by the standards of the day, but as these standards are ina permanent process of evolution we can never be exactly sure what it iswe are censoring and why. For instance, Ron Oliver makes photographs of,by and large but not exclusively, young girls, often pictured with theirmothers or fathers. The photographs are commissioned by the parents anda number have been published as a collection in As Far as the Eye Can See.However, in 1992 Oliver was arrested by the Obscene Publications Squadon charges of producing child pornography, and had much work confiscatedwhich has yet to be returned. If we look at Oliver's Threesome it is hardto distinguish what it is that is either obscene or pornographic or shouldneed censoring. There is a pregnant mother and a young daughter, both ofwhom are naked, and the tumescent bump of an unborn baby. The mother kissesthe child and the child embraces the mother. The obvious relationshipsset up between the experienced mother, the young girl and the baby speaksimply and eloquently of the human cycle of reproduction, nurturing anddevelopment. There seems nothing degrading or horrific about this image:on the contrary, it is a touching portrayal.

One possible explanation as to whywe find images of the pubescent body so problematic could be located inour reluctance to be reminded of the loss of our own innocence, and theinevitable consequence that is our often difficult, 'grown-up', sexuality.If as a society we are suffering from a fin de millénaire wearinesswith the difficulties of being members of what appears to be an increasinglyunstable community it is natural that we should develop, as an antidoteto the more unpleasant aspects of everyday life, a desire to preserve whatwe perceive as, in the absence of religious certitudes, expressions ofhumanity untainted by the cynical and superficial aspects of the late TwentiethCentury. Hence the value of the child in society as a signifier of ourhopes for the future. A more faithful, and more honest, filmic adaptationof Lolita would have used a younger actress, a child who could actuallyconvey the impression of youth intended by Nabokov, but in the currentmoral climate we should not be surprised that Adrian Lyne has acted ashis own censor in order to avoid the hue and cry that would surely havegreeted the appearance of a genuinely juvenile Lolita.

Eye Of The Beholder Film

Notes

1 The Daily Mail, Friday April 241988, p. 1 and 7

2 There are so many themes thatarise in connection with the main subject of this essay that inevitablyin a relatively small space I can hope only to articulate a small proportionof them, so the reader must bear in mind that I am in no way presentingmy feelings here as an open and shut case.

3 Of interest on this subject isMark Sladens' 'School for Scandal', Art Monthly, no. 201 November 1996,pp. 12-14

4 Sally Mann is the exception as,while producing photographs that are both provocative in their depictionof unashamed nakedness and haunting in their beauty, she has so far notsuffered at the hands of either moral zealots or the authorities, perhapsbecause the children she has photographed are her own and, as interviewsand documentaries have shown, entirely undamaged by the process of photography.

Comments are closed.